Humbolt County gets the green light: How business is changing as America’s marijuana epicenter goes legal.

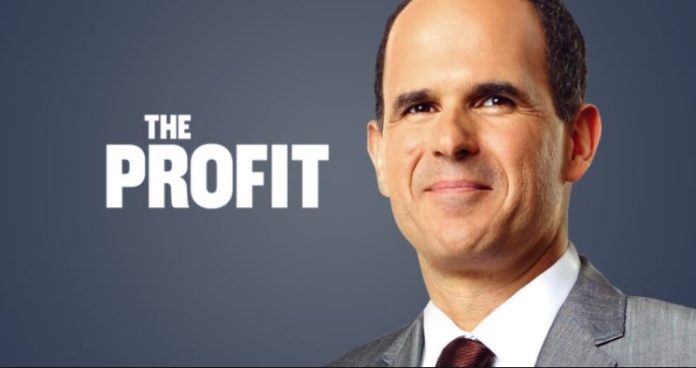

Next on | The Profit in Marijuana Country from CNBC.

In November 2016, voters in California approved a ballot measure known as Proposition 64, legalizing adult recreational use of marijuana statewide. The initiative, which took full effect on Jan. 1, will make California the largest legal pot market in the world.

For decades, California has been home to a massive black market cannabis industry, supplying as much as 70 percent of the nation’s marijuana. The historic epicenter of that industry and of America’s pot culture in general is remote Humboldt County — a rugged coastal region 200 miles north of San Francisco. It is here, at the end of twisting mountain roads, nestled in dark redwood forests, that homesteaders have grown marijuana by the truckload for several generations.

Starting with the “back-to-landers” and free-spirited hippie movement in the late 1960s, growers refined the science of pot farming here. Years of genetic cross-matching and plant testing led to the perfection of dozens of separate THC-heavy strains, catapulting the Humboldt pot business into a billion-dollar industry. While medical marijuana has been legal in California since 1996, the vast majority of Humboldt County pot has been a black market product — illegally grown and illegally sold.

With the passage of Prop 64, there’s one question on the minds of many residents here – how will the legalization of pot affect the wider economy of Humboldt County? Will the green gold in the hills ever flow down to Main Street?

On the dim thoroughfares of Eureka, Humboldt County’s largest population center, there are scant signs of a massive, ubiquitous industry. Homelessness and vagrancy are prolific. The crime rate is high. In the downtown historic district, there is a scattering of high-end restaurants and upscale boutiques, but a few blocks over, the cityscape changes to boarded up buildings and fleabag motels.

On the dim thoroughfares of Eureka, Humboldt County’s largest population center, there are scant signs of a massive, ubiquitous industry. Homelessness and vagrancy are prolific. The crime rate is high. In the downtown historic district, there is a scattering of high-end restaurants and upscale boutiques, but a few blocks over, the cityscape changes to boarded up buildings and fleabag motels.

“Based upon the billion dollars that’s generated here, our streets should be lined with gold,” said Humboldt County Sheriff Billy Honsal.

That paradox applies to the rest of Humboldt County. This area is rife with poorly maintained roads, schools that appear to be dilapidated, and underfunded municipal services. On paper, Humboldt is one of the poorest counties in California, with a poverty rate well above the national average. And yet, the hills of this region are dotted with multimillion-dollar cannabis farms. So what gives?

Honsal says a big part of the problem is the banking industry, which is federally regulated, and still largely inaccessible to cannabis related businesses. Simply put, banks have long shunned marijuana money, fearing federal consequences. “Where can they put this money?” said Honsal.

“Lots of money’s leaving here. It’s going all over the world. There are people here that have invested in marijuana here so they can support industry elsewhere. I’ve heard of people buying houses in the Grand Caymans. I’ve heard of people buying property in South America with their marijuana money,” Honsal said.

In Humboldt County, cash is king. Because of federal law, growers face hurdles taking out business loans or establishing equity through the U.S. banking system. And yet one study showed that one out of every four dollars circulating in Humboldt is directly tied to the cannabis industry. In a place where even the local utilities have cash counting machines at every counter, the money may flow down from the hills, but not in the ways you might expect.

“We have a very generous community here,” Honsal said, noting that local nonprofits and community organizations are heavily reliant on the generosity of local pot growers. Deep pocketed donors often show up at school fundraisers with bags full of cash, he said. But it’s a haphazard arrangement, and hardly reliable.

Honsal is hopeful that the influx of tax revenue from the legalization of cannabis will institutionalize the community benefits of the pot industry. Humboldt County is set to receive $7.3 million in marijuana excise tax revenue in the coming fiscal year, a portion of which Honsal intends to use to hire two new deputies for his drug enforcement unit.

Another sector of the economy already changing dramatically as a result of cannabis legalization is the real estate market. A pot real estate boom is a direct result of legalization. With a diminished risk of arrest or confiscation, Humboldt pot properties are increasingly attractive to outside investors. Money is flowing into the market from Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and overseas.

Still, a certain amount of risk remains relating to all the marijuana businesses in California and in any state where it has been legalized, as the federal government still considers pot to be a Schedule 1 drug. In the eyes of the feds, pot is still illegal.

Dana Wallace is a new breed of real estate broker. For 15 years she’s sold land in California. In the past year she’s transformed her portfolio completely. She now exclusively represents cannabis related properties through her company “420 Estates.”

“I saw the potential, and I saw these properties that these investors were going to start going after,” Wallace said. “And somebody’s gotta do it, so it was kind of a natural path.”

Wallace views the Humboldt County real estate boom as a lucrative opportunity, but she admits there are impediments. Federal banking regulations have made it nearly impossible to get a mortgage on a cannabis related property. That won’t change as long a pot is federally illegal. No matter how profitable the planting cycle appears, if an investor is forced to tie up millions of their own dollars in an unstable regulatory environment, it’s still a risky bet.

The pot real estate boom in Humboldt County is not confined to large outdoor growing properties. In anticipation of the passage of Prop 64, the Eureka City Council passed an ordinance allowing for cannabis related businesses in the industrial areas of the city. While much of this cannabis zone is awaiting approval from the California Coastal Commission, there is currently a two-block area open for new pot related businesses. Known by locals as “extraction alley,” for the processing of marijuana concentrates that happens here, this neighborhood has also seen a proliferation of indoor cultivation and pot distribution facilities.

Rob Holmlund, director of community development for Eureka, supports the city’s cannabis zoning change, in part because of the diminishing prospects of the area’s historic industries.

“The timber industry peaked in 1959 and the fishing industry peaked in the 1970s. And so both of those industries have been on a decline since,” Holmlund said. “Cannabis can add to the diversity of our economy.”

But some in Eureka are concerned that the city is placing too big a bet on cannabis.

In the months since the new ordinance passed, “extraction alley” has been flooded by pot-related entities, which, in some cases, have displaced longtime Eureka businesses. Adam Dick is a co-owner of Dick Taylor Craft Chocolate, one of the last remaining non-cannabis businesses in the area. Dick still has two years left on his lease at 65 cents a square foot. But neighboring businesses, including a sports supply company, an auto repair shop, and a metal recycling facility, have been evicted or priced out, as buildings in the zone are now renting for as much as $3.50 a square foot.

“I think initially when we were in this building we thought, okay, we’ll stay here for a long time, and then maybe we would expand into another warehouse, and kind of be able to scale the size of our business that way,” Dick said. “But now with rents being so high in this area, now I think we’re feeling a little bit landlocked.”

He is concerned that when his lease is up, his chocolate company may be forced to relocate, possibly out of Eureka entirely. “It’s certainly something that keeps us up at night.”

Just down Route 101 from Eureka, the quiet town of Fortuna is taking a different approach to marijuana. In May 2017, the Fortuna City Council drafted an ordinance to bar commercial cannabis businesses within the city limits.

Erin Dunn, CEO of Fortuna’s Chamber of Commerce, told a local radio station: “It feels like our soul has been lost in an honest attempt to create a business-like environment for the pot growing industry. We should stop and regroup, but the tidal wave of cannabis is overtaking us, and we are fighting the rising tide with wading boots and umbrellas. We are going to get soaked.”

But even in conservative Fortuna, which is positioning itself as a “sanctuary city from cannabis,” the economic clout of marijuana is hard to ignore.

Cara and Greg Knostman run Lotus Mountain Custom Screen Printing on Fortuna’s Main Street. For more than 20 years, they’ve printed t-shirts, decals, and hats for local Humboldt County businesses. Since the passage of Prop 64 in November, the Knostmans’ business has expanded like never before. Promotional products for local pot businesses now account for about 35 percent of Lotus Mountain’s total business, a client sector that was virtually nonexistent five years ago. With dozens of cannabis businesses emerging from the shadows, Lotus Mountain expects to see $1 million in sales this year.

Cara Knostman says Lotus Mountain is not unique. She feels that every business on Main Street is already benefiting from marijuana in one way or another. “Whether people want to admit it or not, [cannabis] is the No. 1 money maker in this county. And that’s my thing, bring the people out of the shadows. Have them start paying taxes,” Knostman said. “There’s a lot of potential, but if we don’t bring those people into the light and into the conversation, then places get left behind.”

Whatever approach the towns and cities of this region settle on, Humboldt County, and by extension the state of California, is about to embark on a massive free market experiment, the impact of which will resonate in every corner of society. The starting line is New Year’s Day. The winners and losers are yet to be determined.

“The Profit in Marijuana Country” premieres on CNBC Tues. Jan. 2 at 10 p.m. ET/PT.